Don Ashley opens a plexiglass chamber, closes a Kindle e-reader inside it, and unleashes a rainstorm. Waterdrops pelt the device while he monitors for any changes to the screen and other components. "We think of it as research and destruction. Because we destroy things, and then we research how to make them better," said Ashley, a senior hardware reliability lab engineer at Amazon's Lab126.

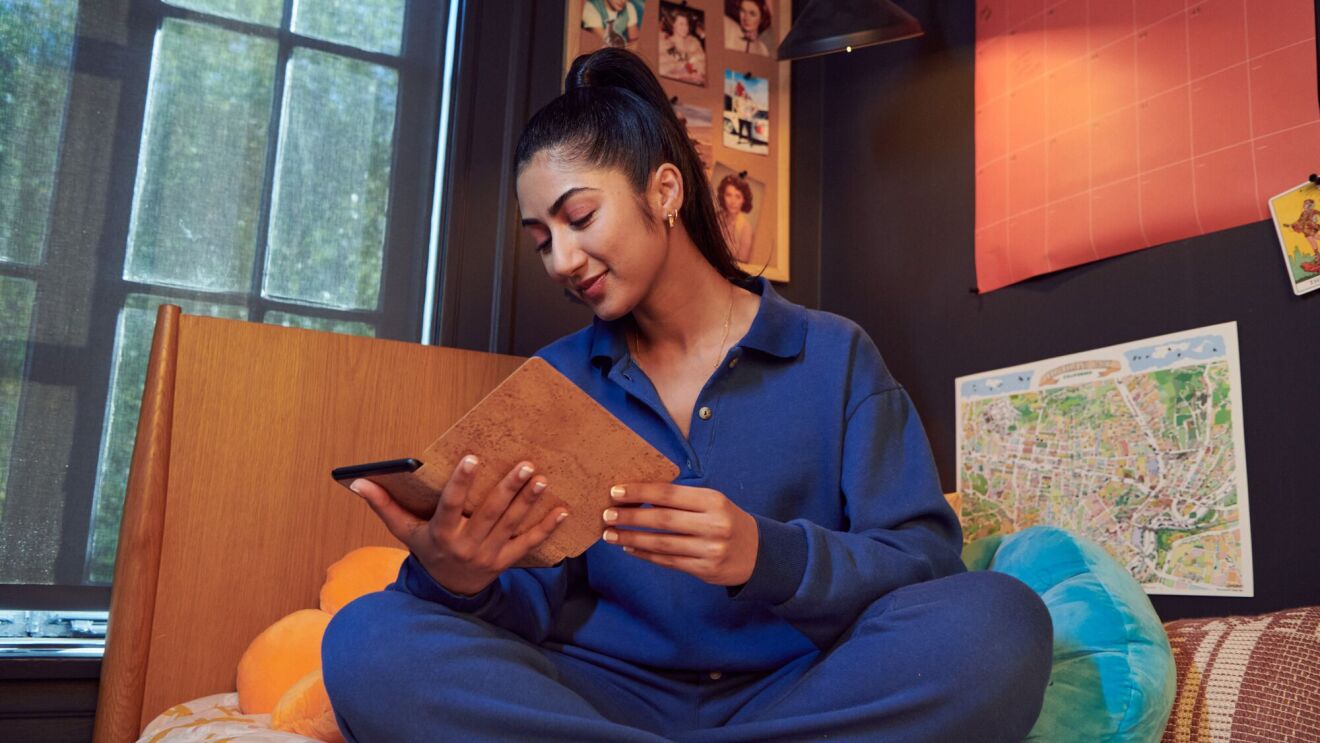

Located in the San Francisco Bay Area, the team at Lab126 designs and engineers Fire tablets, Kindle e-readers, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Echo, and other devices.Photo by JORDAN STEAD

Located in the San Francisco Bay Area, the team at Lab126 designs and engineers Fire tablets, Kindle e-readers, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Echo, and other devices.Photo by JORDAN STEADHeadquartered in Sunnyvale, California, Lab126 started more than 15 years ago when Amazon had a vision: to improve upon the physical book, making it easier than ever for customers to discover and enjoy the written word. Gregg Zehr, vice president of hardware engineering at Palm Computing at the time, was part of the group that accepted the challenge. In October 2004, Zehr formed a small team, moved into a shared space in a law library, and got to work. Lab126 was born. The lab's name originated from the arrow in the Amazon logo, which draws a line from A to Z in "Amazon." In Lab126, the 1 stands for "A" and the "26" stands for "Z."

After years of research and development by Lab126, Amazon launched the first Kindle e-reader on November 19, 2007. It sold out less than six hours after it went on sale. The Lab126 team has expanded rapidly since then, with Zehr as its president. The team designs and engineers a variety of new, innovative products in addition to Kindle e-readers, including Fire tablets, Fire TV, and Echo devices.

The Lab126 facility, where Ashley does his "research and destruction", exists because the world is a tough place for devices. We've all dropped cell phones. Maybe you left your Kindle on top of the car, or in the sand at the beach. Maybe the cat knocked your Echo device off the counter. "We want to make sure that doesn't mean that's the end of that product's functionality," Ashley said.

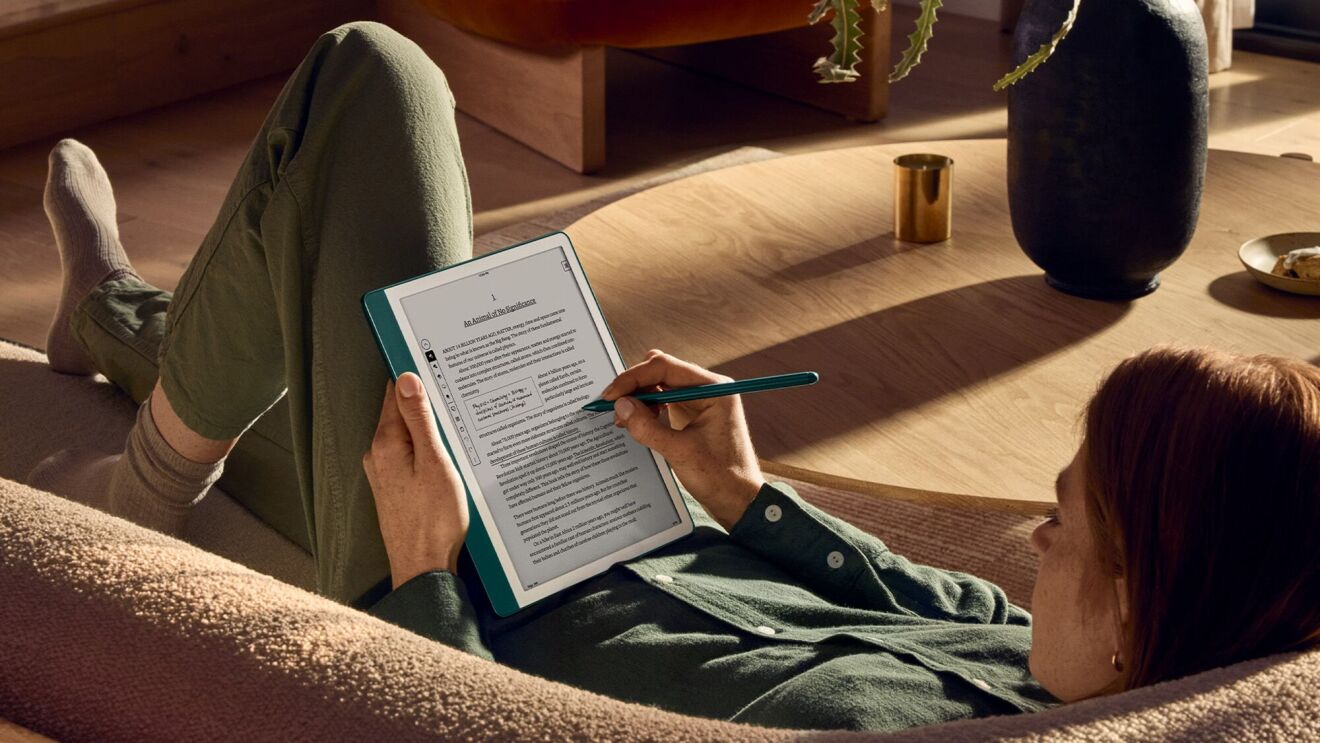

In addition to rain, engineers test for weather conditions from extreme heat and humidity to extreme cold. Amazon's devices are also subjected to twisting, squeezing, power cord yanking, vibration, and altitude testing. There's even a dunk tank to simulate when a customer drops their Kindle into water. Other tests are meant to replicate random impacts: cameras capture the crash landing of an Echo device in the drop tester, and a Fire tablet rolls through the tumble tester, a machine that resembles a spinning carnival ride, minus the safety belts.

"When I see these things hit the deck and they're bending, I'll review it later in the high-speed video playback. I see how much movement there is, warping and twisting. It intrigues me in almost a primal way," Ashley said.

He has facilitated testing on thousands of Amazon devices, including the first Fire tablet, since joining Lab126 in 2011. Through failure analysis, he and his team leverage state-of-the-art tools to analyze how a device broke. "We can then turn around and say, 'how can we make it stronger?'"

The engineers also perform materials analysis. For example, they'll study the plastic case of a Kindle to make sure it's not too soft, not too hard, not too slippery. They'll test how it holds up to common personal care products like sunscreen or hair gel. And for those moments when you're eating while reading—things like olive oil, mustard, even red wine. "We don't want the product to stain, we don't want it to warp or degrade or turn funny colors. We want the customer to have a good, happy experience with all our products," Ashley said. "It's empowering, being able to bring forth a good product for customers and for Amazon. It makes me proud because that means I've done my job."

01 / 08

Trending news and stories