- 2025 Cohort of the Writers’ Access Support Staff Training Program Announced

- Amazon and Cochlear collaborate to pioneer a solution that brings delight to the TV watching experience for people globally who use hearing implants.

- Amazon is providing opportunity, tools, and services to help selling partners and small businesses reach hundreds of millions of customers around the world.

- Making inclusive choices behind the camera and in the boardroom ensures we are delivering meaningful, authentic content to our customers around the world.

- Amazon has been working to make its products accessible to everyone for a decade, and the company is just getting started.

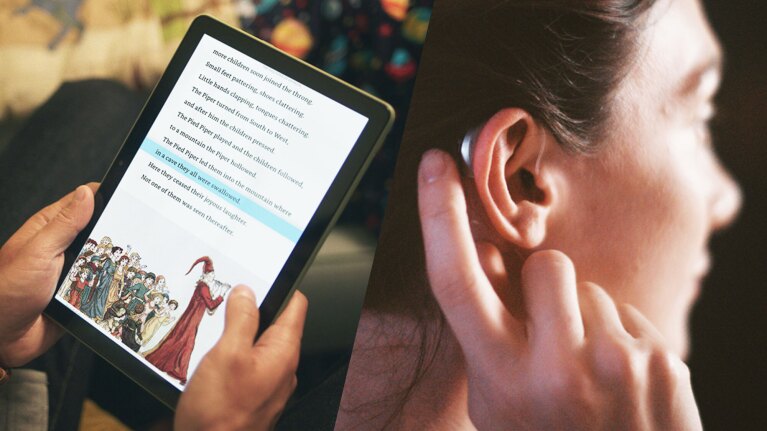

- Amazon is introducing new accessibility updates, including a Dual Audio feature, expanded hearing aid support, and new tactile device packaging.

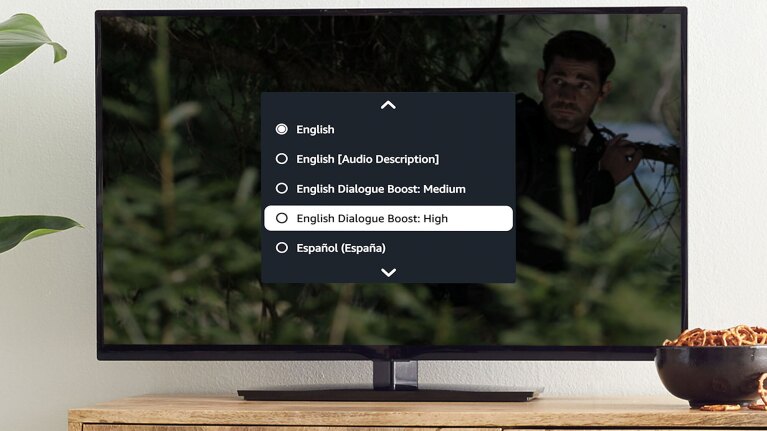

- Dialogue Boost is an innovation that lets you self-select dialogue volume levels to suit your needs on any device with Prime Video.

- Local entrepreneurs in Seattle learn how to build apps in minutes and save time on their day-to-day tasks thanks to PartyRock, a free generative AI tool from Amazon Web Services.

- In 2023, independent sellers in the U.S. grew sales to more than 4.5 billion items—an average of selling 8,600 items every minute—and averaged more than $250,000 in annual sales.

- Plus, get buzzy updates on ‘Cross’ from star Aldis Hodge, and ‘Tyler Perry’s Divorce in the Black' from leads Meagan Good and Cory Hardrict.

- Customers in South Africa can now shop from a wide variety of local and international brands, take advantage of great prices, and enjoy same-day and next-day delivery.

- Veteran and Amazon employee, Mike Williams shares how he helps support veterans with disabilities and address homelessness and mental health.

- Amazon is committed to building a sustainable business for our customers, communities, and the world, and this focus extends to Project Kuiper.

- In Paraisópolis, the second largest favela in São Paulo, customers can get their Amazon packages quickly, thanks to a logistics network that relies on AI and ML to deliver to these vulnerable communities—places where most online retailers don’t offer package delivery.

- We met with sign language interpreters who helped make the ‘Amazon Music Live’ concert series more accessible. Here’s what they want you to know about their work.

- Meet the teams working to make more effective tools for customers and employees with—and without—disabilities.

- Amazon cosponsored National Small Business Week for the fifth consecutive year.