Neuroscientists have been working at it for decades, but progress on treating brain diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s is slow going.

Why? The brain is our most complex organ. It’s also the most inaccessible to study. Datasets gathered for brain research are extensive, but disparate—and they often don’t exist in a universal scientific language.

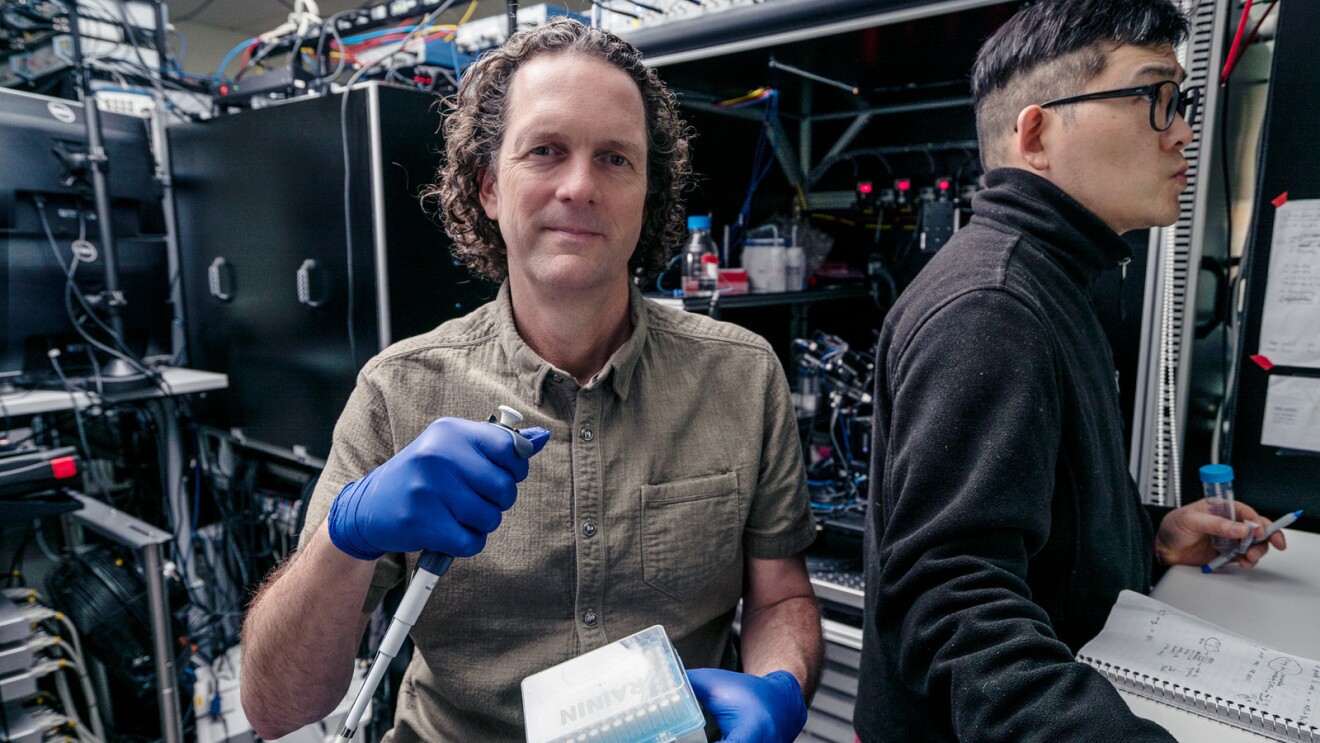

Rebecca Hodge, Ph.D., assistant investigator, Allen Institute for Brain SciencePhoto by Erik Dinnel, Allen Institute

Rebecca Hodge, Ph.D., assistant investigator, Allen Institute for Brain SciencePhoto by Erik Dinnel, Allen Institute“Despite a huge amount of investment, we haven’t yet come up with solutions for the main brain disorders,” said Ed Lein, a senior investigator at the Allen Institute for Brain Science. “We’re awash in information, but it’s not centralized or synthesized.”

With funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and technology from Amazon Web Services (AWS), the Allen Institute is leading an effort to change this—by building something called a Brain Knowledge Platform.

One part of the brain knowledge platform work, led by Lein and a network of neuroscience researchers from 17 institutes across the world, will be to make a new map of the entire brain at cellular resolution. The other part of the effort, led by the Allen Institute’s head of data and technology, Shoaib Mufti, in collaboration with AWS, will be to use this brain map to create the largest open source database of brain cell data in the world. It will be the first of its kind to compile and standardize massive datasets on the structure and function of mammal brains.

The ultimate goal is to create a resource that will enable better diagnosis and treatment of the mental and neurological disorders and diseases that affect more than one-fifth of America’s population, costing the U.S. economy $1.5 trillion a year.

“Chemistry has the periodic table. Genomics has the human genome map, which has been transformative. Neuroscience needs a similar foundational resource, which the brain knowledge platform will help to create,” Lein said.

Ed Lein, Ph.D., senior investigator, Allen Institute for Brain SciencePhoto by Erik Dinnel, Allen Institute

Ed Lein, Ph.D., senior investigator, Allen Institute for Brain SciencePhoto by Erik Dinnel, Allen InstituteThe workhorse of the platform is single-cell genomics. Thanks to new technologies that measure the genes being used within individual brain cells, researchers can now better understand the brain’s cellular complexity and the genes that give cells their distinct functions. These highly detailed cell atlases will help researchers understand the origins of disease and, eventually, allow clinicians to pinpoint why diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s occur.

“This knowledge platform will enable researchers to make new discoveries that are not possible with current infrastructure,” said Mufti. “Once we start to connect pieces of information together, and we can connect data from the healthy brain to information from a diseased brain, that's where the magic is going to happen.”

The platform also draws connections across brain research in different species, and Lein expects that the knowledge graph will eventually integrate information across all mammalian biology.

Cloud computing is what’s enabling data from the brain’s approximately 200 billion cells to be stored, analyzed, and accessed as an open source tool that will ultimately be used by the clinicians seeking treatments and cures for brain diseases. High performance computing on AWS and Amazon SageMaker are helping the Allen Institute manage all this data, scaling across multiple workloads. The institute is using AWS’s artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) services—and plans to implement generative AI in the future—to transform large, complex multimodal data into usable insights for doctors.

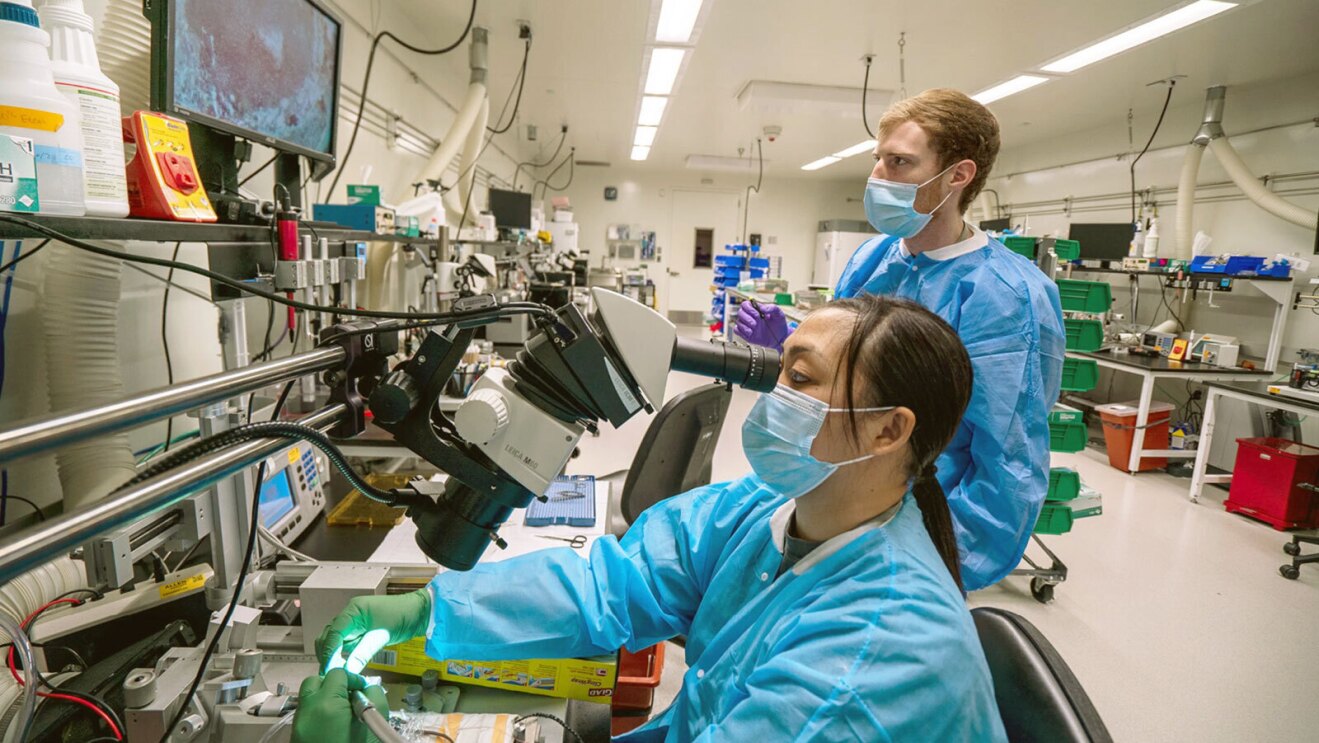

Researchers from the Allen Institute for Brain SciencePhoto by Erik Dinnel, Allen Institute

Researchers from the Allen Institute for Brain SciencePhoto by Erik Dinnel, Allen Institute"AWS machine learning empowers research organizations to uncover new connections and discoveries with purpose-built AI services," said Allyson Fryhoff, managing director of AWS nonprofit and nonprofit health. "Allen is using advanced cloud technologies like ML to further accelerate their findings in a cost effective and scalable way. We're inspired by their work to unlock never-before-seen insights about the human brain, and we look forward to the many brain research breakthroughs to come."

David Van Essen, a professor of neuroscience at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, and an Allen Institute research partner, has been studying the brain for more than five decades. He likens the quickening pace of brain research to the evolution of geospatial mapping.

“Centuries ago, we had colorful but rather crude maps of what people thought the Earth’s surface looked like. Cartographers knew roughly where the continents and islands were, and what the major geographic and political subdivisions were, but they were not very accurate,” Van Essen said. “Recently, there's been an explosion of information and better technology with satellite images and vastly more accurate and user-friendly navigation tools. What we aspire to do for the human brain is to get better and better maps with greater and greater detail, which will become powerful navigational tools for brain disorders.”

Lein and his team are just beginning this five-year project to map the human brain, which, much like the Human Genome Project before it, has the potential to open new doors—not just in neuroscience, but all of medicine.

Trending news and stories

- Amazon CEO Andy Jassy shares the simple question that helps power Amazon's innovation

- Amazon will share its Q1 2025 earnings on May 1

- The Amazon Book Sale is back April 23-28 with thousands of deals across books, select devices, and memberships

- Amazon CEO Andy Jassy shares how AI will reinvent ‘virtually every customer experience we know’