Buildings, roads, and sidewalks are all impervious surfaces, which means they do not allow water to seep through. That also means such infrastructure is a major factor in urban flooding. One solution could be green infrastructure.

Amazon Web Services’ (AWS) podcast Fix This recently welcomed Christopher Kennedy, assistant director of the Urban Systems Lab, and research fellow Pablo Herreros Cantis, to discuss green infrastructure and the technology aiding their research. They say green infrastructure has the potential to address environmental injustices and help vulnerable populations by reducing urban flooding risks related to climate change.

“In general, in a lot of U.S. cities, there's a long history of banking institutions, mortgage institutions, not providing the resources for certain communities,” said Kennedy. Herreros added: “And it has been shown already, with relative consistency, that formerly redlined neighborhoods and neighborhoods that have a higher percentage of minority populations have more impervious surfaces.”

The Urban Systems Lab, which is based at The New School in New York City, focuses on research and providing new insight into developing more equitable, resilient, and sustainable cities. The Lab is focused on helping municipal governments better plan where to implement green infrastructure investments.

Through the Lab’s Environmental Justice and Green Infrastructure Research project, a project supported by the Kresge Foundation’s CREWS program, Kennedy and Herreros are currently working with local non-governmental organizations, such as Groundwork USA, and communities in the U.S. The implementation of green infrastructure to address issues such as flooding provides several ecological functions—including infiltration, evaporation, and other natural processes—to handle storm water that would otherwise flow into urban drains or sewers. Through green infrastructure, water is instead absorbed by soil or moved below the surface, or it evaporates.

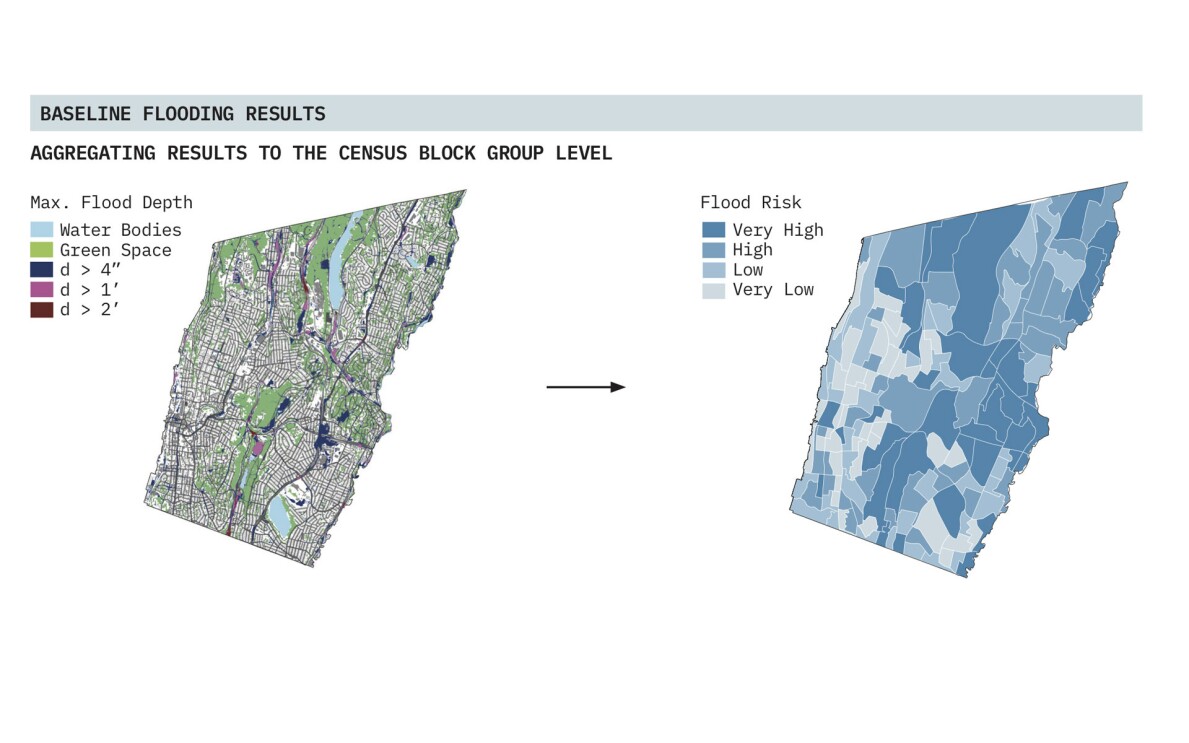

The team is currently examining the disproportionate effects of urban flooding and climate change on minority and low-income communities in four small- and medium-sized U.S. cities: Syracuse and Yonkers, New York; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and Elizabeth, New Jersey.

Herreros said the Lab selected the cities based on commonalities, including, “We were looking for locations in which we were going to be able to connect with organizations or municipal governments that would be interested in collaborating.”

Socioeconomic factors that create vulnerabilities also play a role in urban flooding, such as poverty, a lack of health insurance, and access to green space. Kennedy and Herreros note that when existing social disparities overlap with extreme weather events, they can compound harmful outcomes.

The Urban System Lab integrates those social variables into its analysis and proposed solutions. The Lab takes an interdisciplinary approach by bringing together designers, scientists, and practitioners to work on complex questions about how cities interact with different ecological, technological, and social systems.

When Herreros initiated model simulations to investigate the root causes for why urban flooding more heavily impacts certain communities, he quickly realized that the simulations would require more computational power to complete the project and accelerate the research. With support from the Amazon Sustainability Data Initiative (ASDI) and AWS Promotional Credits, the Lab’s simulations now run on the AWS Cloud.

“What we have so far been exploring in our work is focused on the distribution of current flood risk,” Herreros said. However, he noted: “It's not only what is happening now, it's also where are we heading and how we need to consider that we need to make very cautious decisions on how to adapt climate change in a way that doesn't leave anyone behind.”

To learn more, visit AWS Sustainability Customer Stories for a multimedia look at how AWS customers are building in the cloud to innovate, expedite, and scale real-world sustainability solutions.

Subscribe to Fix This on Spotify to stay up to date on the latest Fix This episodes, featuring customers from around the world that use AWS to solve some of the world’s most pressing challenges.

Trending news and stories

- Meet Project Rainier, Amazon’s one-of-a-kind machine ushering in the next generation of AI

- What’s new for Prime Day 2025? 4 things that make this year’s event different

- See Judge Judy Sheindlin in the trailer for ‘Justice on Trial,’ coming to Prime Video

- How to watch every ‘Jurassic Park’ movie on Prime Video