At its simplest, a data center requires three things to work properly. The first is a building, the kind of thing that can protect the servers from rain, snow, and even tumbleweed. The second is power, the juice that keeps all those servers running.

The third is cooling. This is the element without which those servers could overheat and shut down in a matter of minutes. It’s also the one Amazon Web Services (AWS), and the entire data center industry, is in the midst of transitioning from an air-based to a liquid-based solution.

The shift, happening across parts of the AWS portfolio, matters because there’s actually a fourth thing a data center needs: the ability to evolve. Last year AWS announced it would be rolling out new data center components designed to support the next generation of artificial intelligence innovation and customers’ evolving needs.

The shift from air to liquid cooling plays a vital role in that adaptation.

Tipping points

Before diving in, it’s worth noting that while “cooling” may suggest the kind of air conditioning you enjoy at home or in the office, data center cooling is different.

“We call it cooling, but our goal isn’t a comfortable, 68-degree data hall. Our goal is to move just enough air through our servers to keep them from overheating, and use the lowest amount of energy and water to do that,” said Dave Klusas, AWS’s senior manager of data center cooling systems. “In the summertime, that actually means our data halls are pretty warm.”

Until now, air-based systems have been doing this job inside AWS’s data centers. At a high level, it’s a matter of pulling air inside and circulating it through the racks of servers. The air pulls heat off the electronics as it goes and is then sent outside again as more cool air comes in to make the same trip.

But now, air alone isn’t always enough.

With today’s AI chips, some workloads (such as training large language models) benefit from grouping as many chips as possible in as small a physical space as possible. Doing so reduces communications latency, which improves performance and thus reduces cost and energy consumption.

Each AI chip performs trillions of mathematical calculations per second. To do this, they consume more power than other types of chips, and in doing so, generate much more heat. In turn, that requires more airflow to remove that heat. So much airflow, in fact, that it’s not practical or economical to cool the chips using air alone.

“We've crossed a threshold where it becomes more economical to use liquid cooling to extract the heat,” said Klusas.

Turning on the faucet

Liquid cooling is more complex than the air-based approach, but because liquid is more than 900 times denser than air, it can absorb much more heat. It’s the same reason that a dip in the ocean can be so much more refreshing than a breeze on a sweltering day at the beach.

Klusas’s team considered multiple liquid cooling solutions that could be purchased from vendors, but realized none were a good fit for AWS’s needs.

That put them on a path of designing and delivering a completely custom system.

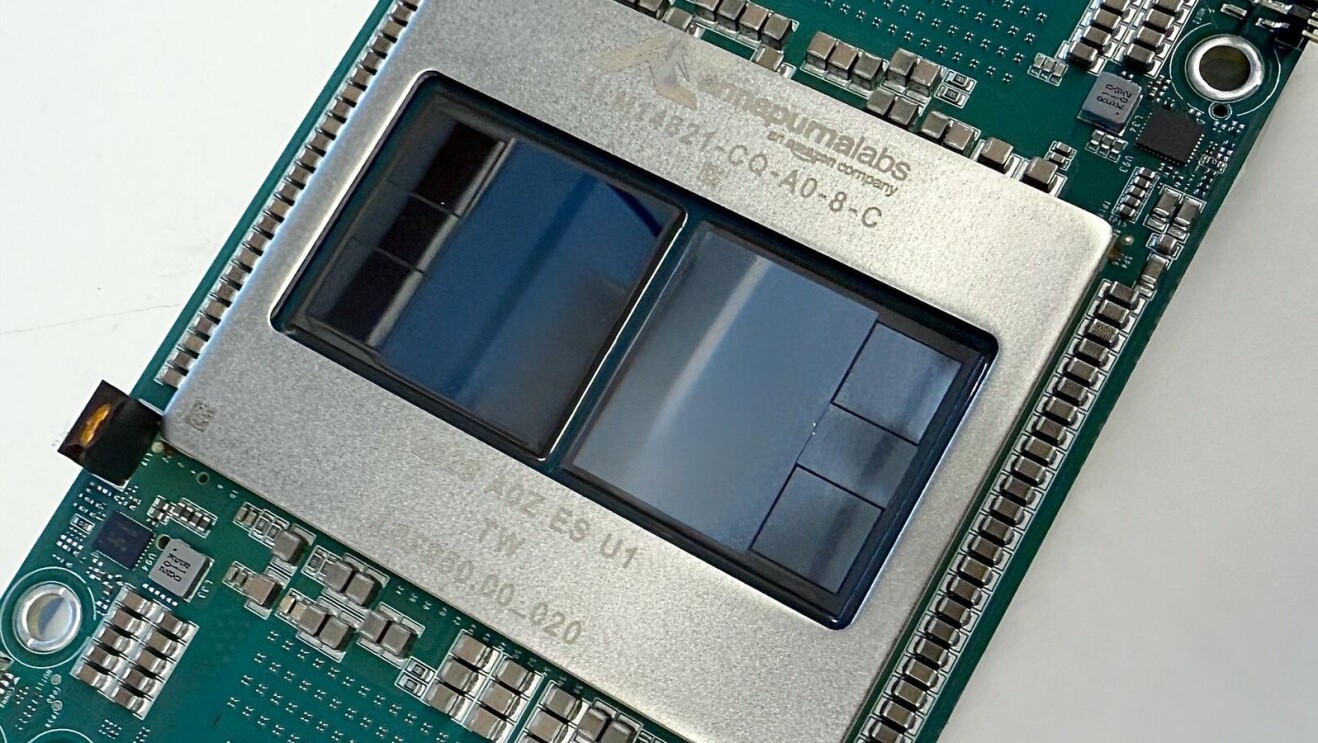

AWS is taking a direct-to-chip approach, which puts a “cold plate” directly on top of the chip. The liquid runs in tubes through that sealed plate, absorbing the heat and carrying it out of the server rack.

From there, it runs to a heat rejection system that cools the liquid (a fluid specifically engineered for this purpose) and then circulates it back to the cold plates. It’s an entirely “closed loop” system, meaning that the liquid continuously recirculates, and—crucially—doesn’t increase the data center’s water consumption.

As with the air-cooling system, the aim is to use just enough liquid to keep servers from overheating, and do so with the least amount of additional energy. This means the liquid is typically at “hot tub” temperatures.

Speed and flexibility

It took just four months for AWS to go from a whiteboard design to a prototype, and then 11 months to deliver the first unit in production. That included time to develop designs, build a supply chain, write control software, test everything, and manufacture systems.

Flexibility is critical because, in the time it takes to build a data center, fluctuating market demands and technological advancements can change the thinking on how to balance liquid with air cooling.

AWS’s designs are built to adapt to changing needs. “We designed our liquid cooling systems to make it easy to add them to data centers where they’re needed, but avoid the expense of adding them where they’re not,” said Klusas.

Another key element of the cooling system is the custom coolant distribution unit AWS has developed, which is more powerful and more efficient than its off-the-shelf competitors. “We invented that specifically for our needs,” Klusas says. “By focusing specifically on our problem, we were able to optimize for lower cost, greater efficiency, and higher capacity.”

Rolling out

Klusas’s team developed the first example of the system at AWS’s research and development center, a lab where the company tests anything and everything that makes it into its data centers. It then deployed test units in production data centers. Now, the system is ready for use at scale. It will be ramped up this summer to take on more and more of the cooling workload, and start moving into other data centers.

How and where it picks up that work will be determined over time, but Klusas is confident in the system’s ability to adapt for a rapidly evolving future. “We’ve created a system that is very energy and cost efficient,” he says, “and can be deployed precisely where liquid cooling is needed to meet our customers’ demands.”

Find out more about how AWS innovation in data centers has resulted in greater efficiency and responsible stewardship of resources.

Trending news and stories